Also Known For : Military Leader, War Hero

Birth Place : Albermarle, Virginia, United States

Died On : February 13, 1818

Zodiac Sign : Scorpio

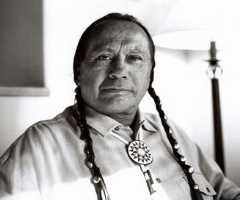

George Rogers Clark Biography, Life, Interesting Facts

Brigadier General George Rogers Clark was one of the heroes of the American Revolutionary War, where thirteen colonies got independence from Great Britain and declared themselves the United States of America. Clark was the highest ranked military officer on the Northwest frontier. His efforts directly resulted in granting the entire Northwest Territory independence from the grasp of the British. The towering figure of American politics, George Mason, regarded him as ‘Conqueror of the Old Northwest.’

Early Life

George Clark was born on 19th of November, 1752 near Charlottesville, Virginia. He had nine siblings and was the 2nd of the ten children. Around 1756, when the French and India War escalated, the family decided to move to Carolina Country from the mouth of action at the Virginia Frontier.

Clark hardly had any formal education – just having a very brief spell at Donald Robertson's school with future United States President James Madison and next Senator John Taylor of Caroline. He was trained by his grandfather in surveying and developed an early interest in it, engaging himself along the Ohio River. He was the surveyor in Kentucky when he was chosen to save it from becoming an independent British colony.

George Clark was subsequently appointed as the captain in the Virginia militia in 1774, and he focused on usurping the British outposts along the Ohio River, thereby curbing the influence of the British among the Indians. For many months, Clark had to defend against unwarranted attacks from the Indian raiders. Clark, as described in his letter to George Mason, patiently planned for long distance strikes against the British.

But soon, tensions escalated to an extreme between the Shawnee and settlers on the Kanawha. This gave way to a war between the American Indian nations and the Colony of Virginia which is famously known as the Lord Dunmore’s War. The conflict ended in the favor of the colonists. Postwar, Clark devoted time to his surveying activities in Kentucky, at the same time making preparations for it to become a county of Virginia.

Becoming a Major

While the American Revolution was taking place, Kentucky was facing an identity crisis of its own. In 1775, land speculator Richard Henderson bought most of Western Kentucky from the native people after signing the Treaty of Watauga. Richard’s motive was to form a separate colony named Transylvania which incensed the dwellers, and in June 1776, Clark and John Gabriel Jones were sent to Williamsburg to calm the situation down.

They hoped to convince Virginia by delivering a petition to the General Assembly to officially have its boundaries extended to include Kentucky. They met Governor Patrick Henry and convinced him to create Kentucky County in Virginia. George Clark was only 24 when he was appointed a major in the Virginia militia, and people looked up to him.

Achievements

George Clark decided to capture two Mississippi River settlements—Kaskaskia, Cahokia and Vincennes both in present-day Illinois. This secret expedition got the sanction from Governor Patrick Henry, and Clark raised his army from Pennsylvania and North Carolina.

In July 1778, Clark led an expedition of 175 men and captured Kaskaskia on the night of July 4th. The same fate awaited Cahokia which was captured five days later. Both the villages were subjugated without even firing a single shot. Several British-held villages and garrisons including the one at Vincennes on the Wabash River were subsequently subdued, although Hamilton retook the Vincennes garrison in December and renamed it as Fort Sackville.

With the advent of winter, Hamilton took a safety-first approach and released most of his men. Clark had an intuition that Hamilton was preparing for a surprise attack come spring to retake the two Illinois forts, and thus he set out on a mission which is undoubtedly his most significant achievement.

George Clark embarked on a deadly trek of a 180 mile march to retake the fort in Vincennes. The regiment of 170 odd men endured calamitous weather, encountering torrential downpour and severe snowfall along the way. Hamilton eventually gave in to the surprise attack where Clark tricked him into believing that he had a large army by strategically attacking from both sides and the garrison was surrendered on February 25th

Other wartime efforts

George Clark's primary mission of capturing the fort at Detroit failed as he couldn’t raise the sufficient number of men for such a big expedition. In June 1780, a mixed outfit of British and Natives attacked Kentucky and surrounding areas. Clark retaliated by winning the battle at Shawnee Village in present-day Ohio.

Clark was promoted to Brigadier General in 1781 by Thomas Jefferson, the Virginia Governor. Clark decided to conjure yet another attack on the British forces at Detroit. A small group of men sent by George Washington to aid the efforts was eliminated by the British forces en route, thus ending Clark’s hopes of another attack on Detroit.

In the Battle of Blue Licks, Clark was heavily criticised for not being present at the battle where his men were pounded by the British Forces. He was the senior military officer in the region at the time. Clark took revenge by winning the Battle of Piqua, the last of his major expeditions.

Later Years

When the American Revolutionary War was over, George Clark was only 30. After the war ended, he worked as a superintendent-surveyor from 1784 to 1788, surveying and granting lands to the war veterans of Virginia. In 1785, Clark negotiated the Treaties of Fort McIntosh (1785) and Finney (1786) with the natives, north of the Ohio River.

But the raids were still ongoing, and tension was at a high again triggering the start of the Northwest Indian War. To put an end to the attacks, Clark led an army of 1200 men against the natives in 1786. But it had a premature ending as the lack of supplies caused a mutiny of 300 men and Clark had to abandon the expedition.

Rumors were rife that Clark remained inebriated most of the time during the campaign. Such allegations infuriated Clark, and he demanded an official inquiry. But the Virginia Government denied the request and consequently reprimanded him. This tarnished Clark’s image, and he never led men to battle again.

End Years and Death

George Clark settled in Indiana, but he was burdened with financial constraints. Clark used to finance a lot of military efforts himself and also took loans from friends. But the Government of the day denied any reimbursement, as there were no adequate records explicitly mentioning these things. Clark was awarded many large land grants one of which was a gift of 150,000 acres of land, but whereas he owned large areas of land, he didn’t have resources to develop them. He was forced to transfer many lands to friends and family as the threat of hungry creditors lurked all the time.

Clark was appointed by Edmond-Charles Genêt, the ambassador of revolutionary France, in February 1793. But his efforts to drive away the Spanish from the Mississippi Valley were cut short as President George Washington intervened, citing the reason of violating the nation’s neutrality.

George Clark wrote his autobiography in 1791, but it was posthumously published. For the rest of his life, Clark spent most of his time operating a gristmill. In 1809, he suffered a stroke and fell into a fire. He suffered severe burns on his right leg, and it had to be amputated. After moving in with his brother-in-law, Virginia finally gave Clark a ceremonial sword and a pension of four hundred dollars per year.

President George Washington praised Clark’s efforts during the war which encouraged the alliance with France. Washington also noted that Clark’s achievement was exceptional because he accomplished all those victories without sufficient funds or men.

On February 13, 1818, George Clark passed away after suffering another stroke. He was buried at Locust Grove Cemetery two days later. In 1869, his and his family’s remains were exhumed and moved to Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville.

More Explorers

-

![Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, sieur de La Vérendrye]()

Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, sieur de La Vérendrye

-

![Knud Rasmussen]()

Knud Rasmussen

-

![Meriwether Lewis]()

Meriwether Lewis

-

![Henry Hudson]()

Henry Hudson

-

![Robert Peary]()

Robert Peary

-

![Jacob Roggeveen]()

Jacob Roggeveen