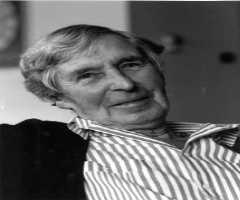

Also Known For : Historian, Educator, Journalist

Birth Place : London, England, United Kingdom

Died On : August 24, 1978

Zodiac Sign : Capricorn

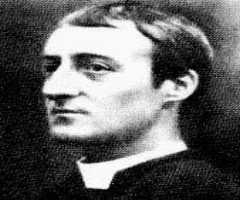

Kathleen Kenyon Biography, Life, Interesting Facts

Kathleen Kenyon was a British archaeologist who is known for her excavation findings in Zimbabwe and the Middle East.

Early Life

Kathleen Kenyon was born to a British aristocratic family in London on January 5, 1906. Her father Sir Frederick Kenyon was an academic scholar and head of the British Museum. She was raised in London next to the London museum. Kenyon went to St. Paul’s Girls School in London. She proceeded to the Oxford affiliate Somerville College. She graduated with a degree in history in 1929.

As a young person, Kenyon was full of energy. She preferred outdoor activities related to the boys. She went fishing and engaged in several sports. In high school, she dominated her class in both academics and leadership skills. She became the head girl in her final year. In college, she played in the hockey team. Kenyon got interested in archaeological history and was elected the president of the college’s archaeological department. Kenyon became the first female student to hold the office.

Archaeological Career

Soon after her graduation in 1929, Kenyon traveled to today’s Zimbabwe with a team of excavators. She viewed the excavation proceedings of the Great Dzimba Dze Mabwe stone ruins as a photographer. In the local Shona language in Zimbabwe, Dzimba Dze Mabwe means the stone houses. She got fascinated by her first experience as an aspiring archaeologist. She returned to England and joined another excavation team to St. Albans. Kenyon observed as the team dug up the Roman era ruins of the town situated to the north of London. She also studied the seemingly more advanced excavation techniques used by the leader Mortimer Wheeler. Kenyon resumed her excavation journeys. She committed her efforts to the Middle East. Kenyon started with the ancient city of Samaria in Syria. She worked in the old city from 1931 to 1934.

She stayed in London during WW2. She volunteered to work with the British Red Cross during the war. She also served as a lecturer in the archaeological faculty of the University of London. After the end of the war, she proceeded to Libya in her quest to excavate new findings in the ruins of the Sabratha. Sabratha was one of the three major cities built by the Romans in Libya. In ancient Roman times, the cities were called Tripolis or the three cities. She documented her findings of the Roman amphitheater like the one she found in St. Albans in England.

In 1949, she moved to Jericho under the invitation of another British historian John Garstang. Garstang had tried digging up the ruins of the city and got mixed findings under the earth. He discovered layers of earth strata which confused his report. Kenyon resumed from where Garstang had left. She discovered that the layers of strata were actually different settlements layering upon the other. The ancient inhabitants built one settlement over the ruins of another. Over a period of thousands of years, the layering of settlements created natural strata beneath the earth’s surface. In the local Hebrew language, such settlements are called Tel.

In her findings, she noted several settlements in the ruins. Just like Garstang, Kenyon concluded that Jericho was the oldest continuously inhabited city since the existence of mankind. She, however, differed with her predecessor on the dating of the settlements. Kenyon suggested the dates to be backdated from the ones Garstang gave. In her opinion, the layers of soil and the historical artifacts, pieces of pottery and bronze pieces dated back earlier than what Garstang presented.

Despite her famous findings and backdating of the given dates, Kenyon stirred up controversy. She disputed the Biblical narrative of the conquest of Jericho by the advancing children of Israel. She said that in her opinion, she found no evidence in the ruins connecting to the story. Her American and Israeli colleagues in the excavation mission in Jericho distanced themselves from the report.

In 1961, she moved from the ruins of Jericho to Jerusalem. She hoped to find great hidden historical discoveries in the holy city. She excavated the old city of Jerusalem starting with the City of David. She turned to the Temple Mount, where she found no hidden treasures for her report. Kenyon moved to Megiddo where she found the stable of Solomon. She also found the foundation ruins of King Herod’s palace. Like in her earlier report in Jericho, Kenyon disputed the claims of Solomon having stables of thousands of horses in Megiddo. She argued that the climate and adjacent terrain was impossible for someone to keep horses as described in the Bible narrative.

Legacy

Kenyon managed to excavate extensively to the deep Bronze Age ruins of the ancient city of Jericho. Her findings of the bronze and pottery artifacts through the Tels is a fete few had achieved in Palestine and greater Levant region. Her disputing of the bible stories has been isolated over the years by other historians, due to her religious and political inclination. Kenyon was an active anti-Zionist. Historians peg her reports to her efforts to nullify the Israelis claim to the land in Palestine.

Conclusion

Since archaeology is a science of interpretation based on the excavations, Kenyon was right to her own sense. As excavations are still being done on a daily basis, only time will tell if her interpretations will stand the test of time.